Book review

Paris in Ruins: Love, War and the Birth of Impressionism

By Sebastian Smee

Norton: 384 pages, $35

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from them. bookstore.orgwhose fees support independent bookstores.

Book review

Monet: the restless soul

By Jackie Wullschläger

Knopf: 576 pages, $45

If you purchase books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from them. bookstore.orgwhose fees support independent bookstores.

Revolution in plenary. During the reign of Napoleon III, the Second French Empire colonized extensively abroad and modernized at home with the creation of the boulevards of Paris and the glorious rise of the city as the world capital of culture and fashion. The Empire brought stability to France after decades of bloodshed and turmoil, but republican passions, especially among the intellectual and political elite, upper middle class.

What happened during the rebellion? This year marks the centenary of the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, and two wonderful books have been created to celebrate. Although they differ in scope, they are beautiful, fluid and resonant additions to the history of art.

The Financial Times critic Jackie Wolschlager has written a lavish biography of Claude Monet, the master of a movement that confines innovation beneath the surface. Monet: The Restless Face spans the artist’s life and career, a portrait of a mercurial and materialistic artist, ambitious and proud, but loyal to all in his orbit. It traces his middle-class background as a child and teenager on the Le Havre seaside, diluting his eternal muse. He chose a poorly paid career with the support of a beloved aunt and best friends such as Edouard Manet. In the 1860s he joined Manet’s circle in Paris: Degas, Basile, Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Pissarro and Renoir. These artists, now stars of museums and private collections, supported each other through the lean months as the rich went on to wealth, united in their disdain for the old norms and the rule of the Salon. (Monet eventually owned 14 of Cézanne’s paintings.)

When the Franco-Prussian War began, Monet went to London, where he sat down in action, palette in hand. After returning to France, he and his colleagues worked outdoors, often setting up their easels side by side. Monet relied on his first wife, Camille, as his primary model; in his first work, “Women of the Garden” (1866), she is depicted as four distinct personalities. Wolschlager notes that “The Port at Argenteuil” (1874), “is a beacon of the early Impressionist moment. Together, each part of the other, inviting the gaze to enter and linger everywhere, in a decorative collection of forms, the arabians of the trees meeting the shapes of the clouds, create a harmonious space that draws on the solid image of a broken bridge is entirely different. a few months ago.”

After Camille’s long illness and death in 1879, Monet married Alice Hoschede, the estranged wife of a department store magnate whose death allowed the couple to marry and reunite their families, the bohemian Brady Bunch. Their villa at Giverny remained a base of operations throughout his life.

Jackie Wullschlager, author of Monet: A Quiet View.

(William Cannell)

Over the course of the century, Monet became bolder: he began several series of subjects depicted at different times of day, with different colours of light. Wohlschlager singles out “Haystacks” as a breakthrough, insisting on “thinking about the passing of that moment, the passing of all moments.” He writes: “Short, choppy strokes create waves of colour in different layers that show the light as a pulsating force, but blend into an impure mist seen from afar.” Against the backdrop of post-war comfort, new ways of seeing emerged.

Wullschläger refrains from attempting a full explanation; why burden his book with useless detail? He prefers to have fun and saves the best for last: his exhaustive study of Monet’s magnificent water lilies (he called them “Grandes Décorations”), wood flames, representation and abstraction, foreshadowing future titans like Pollock and de Kooning. “The Grandes Décorations have the hallmarks of a later style: extreme, abstract, interior,” notes Wolschlager, “at one time the crowning achievement of Impressionism, beautiful paintings … integral compositions that speak of chaos and disintegration.” Despite his poor eyesight, Monet worked until his death in 1926.

Sebastien Smee, author of Paris in Ruins.

(Amber Davis Turlentes)

Washington Post Prize-winner Sebastian Smee builds on Wohlschlager’s approach to Paris in Ruins, focusing on those crucial years before the initial exhibition, when the Franco-Prussian War brought down the Second Empire and gave birth to the Third French Republic. The heart of the book is the romance between Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot, a talented bachelor living with his parents in the pretty suburb of Passy. Manet galvanized inventive (and subversive) artists and writers, drawing them in like a magnet. “He was like the director of an amateur theater group, made up of friends, family and anyone he could connect with,” Smee said. “They wore their assigned costumes with varying degrees of conviction, addressing the audience that was supposedly in on the game.”

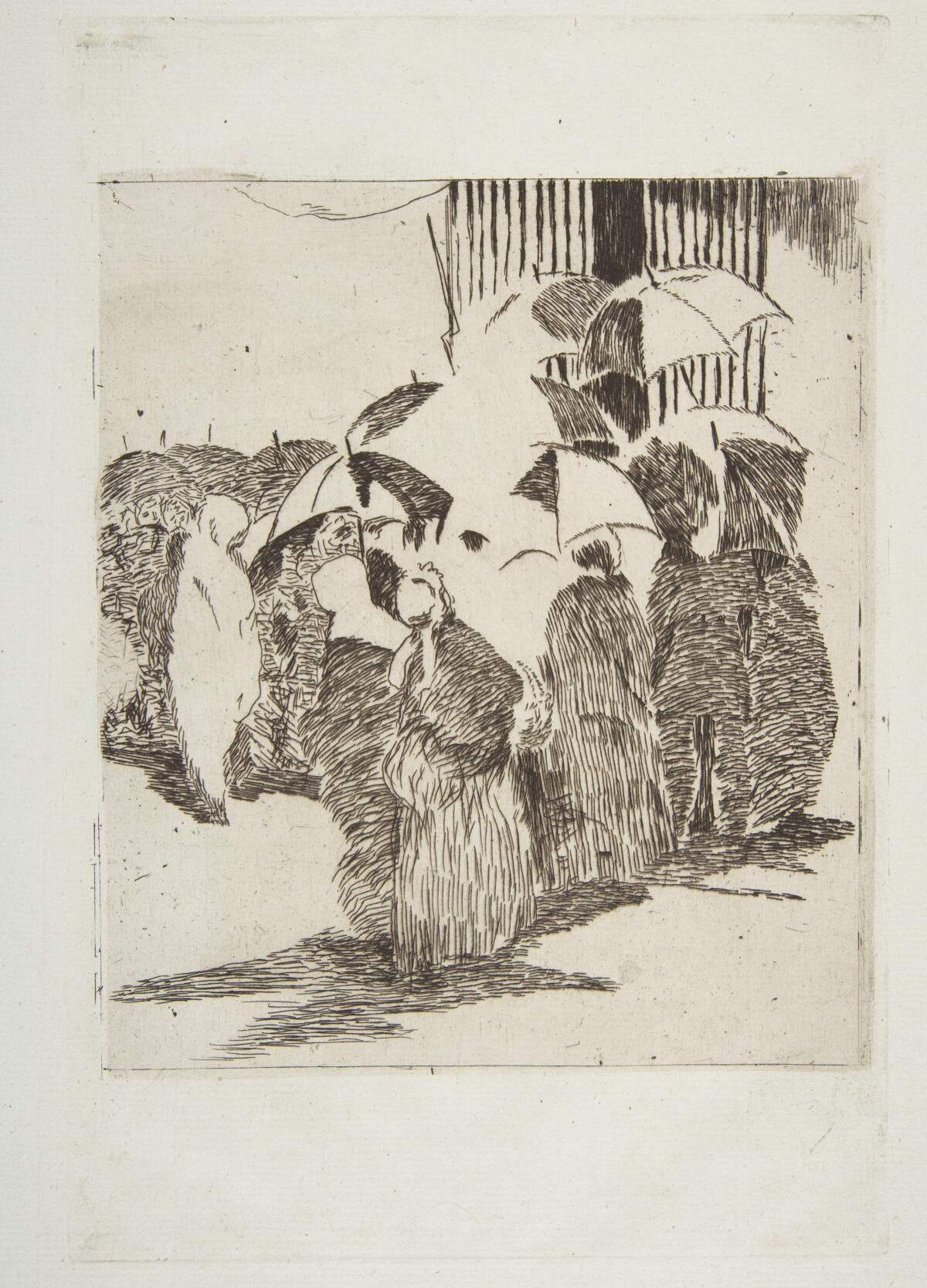

Eduard Manet “Queue in front of the butcher’s shop”.

(Courtesy of Norton)

Manet’s love of Morisot first appeared in his homage to Goya, The Balcony (1868-69). “Paris in Ruins” is full of delightful anecdotes: the Morisots’ fairground gatherings; military duty imposed on legal men; balloons and carrier pigeons that kept the city connected to the world. With an agreement that Napoleon would surrender and end the Franco-German War, civil war broke out in France, pitting leftists against moderates in agreement with the German leader. Smee’s creation of this turbulent moment and the riots that sparked it is a brilliant and moving account, culminating in the Bloody Week of May 1871, which resulted in thousands of civilian casualties, random massacres and the burning of prominent institutions.

As the City of Light came on, this group of artists moved toward tranquil landscapes and domestic scenes that promoted bourgeois values. Yet they were a riot. “The lack of hierarchy extended even to technical considerations: the Impressionists painted directly on canvas, rather than layering varnish over glass or paint,” notes Smee. “Inspired by Japanese prints, they sought to avoid compositions that seemed too calculated, picturesque, or discreetly symmetrical. They welcomed recurring visual phenomena, such as trees covering buildings… Neither shadowed, nor modeled, and therefore lacking in depth. At times “It seemed as if I were viewing these scenes… from a balloon or from a person with only one eye.”” attributed to Mrs. The author claims that her influence was greater than art history has recognized.

Just as the Impressionists freed painting from the strangely academic styles of the Salon, Smee and Wolschlager freed Impressionism from the clichés of bedroom posters and congratulatory sentiments. These artists were and are radical: Picasso rejected their ideas, but it is impossible to imagine him without them, linked through Cézanne, Van Gogh and the Fauves. Both authors find the light at the heart of the movement and amplify it brilliantly on the page.

Hamilton Cain is a book critic and the author of the memoir This Boy’s Faith: Memoirs of a Southern Baptist Upbringing. He lives in New York.